Fantastic Mr. Fox and the decline of children's books

A microcosm of the loss of wonder and the destruction of art that fosters enchantment.

Viewing Wes Anderson’s Fantastic Mr. Fox (2009) recently, I was first struck by its often less-than-subtle critical perspective on the onset of industrial society and its encroachment against nature and community. In Anderson’s telling, Mr. Fox and family’s story begins in a decent burrow, a home proper to the fox. But Mr. Fox’s desire for upward mobility and the finer things in life moves them to a fox hole under an idyllic tree in the woods, fit with a beautiful vista overlooking a spanning valley of fields and orchards. The problem is these neighboring farms in the valley were owned by the three worst farmers, the ‘horrible crooks’ Boggis, Bunce, and Bean. Naturally, a fox being a fox, conflict ensues. A series of escalations, provocations, and altercations ends in tragedy (as Mrs. Fox forewarned). By the end, the foxes and the rest of the animals of the woods are banished to the sewers. Their home had been razed but, in the concluding scene, they discover the fruits of commercial society in the shape of an ‘international supermarket.’ In the end, they are banished from the comforting orange tinge of the wood for the dark, grey gloom of the urban sewers, and made complacent by the easy and sanitized food chain of the city. There’s even somewhat of an economic critique in it: the three farms in the valley are already beholden to the capitalist logic from the start but are still portrayed in the midst of the idyllic countryside. However, at the end, the three farmers leave the local to merge into a, presumably, chain of international supermarkets. It’s actually a tragedy, pretty much.

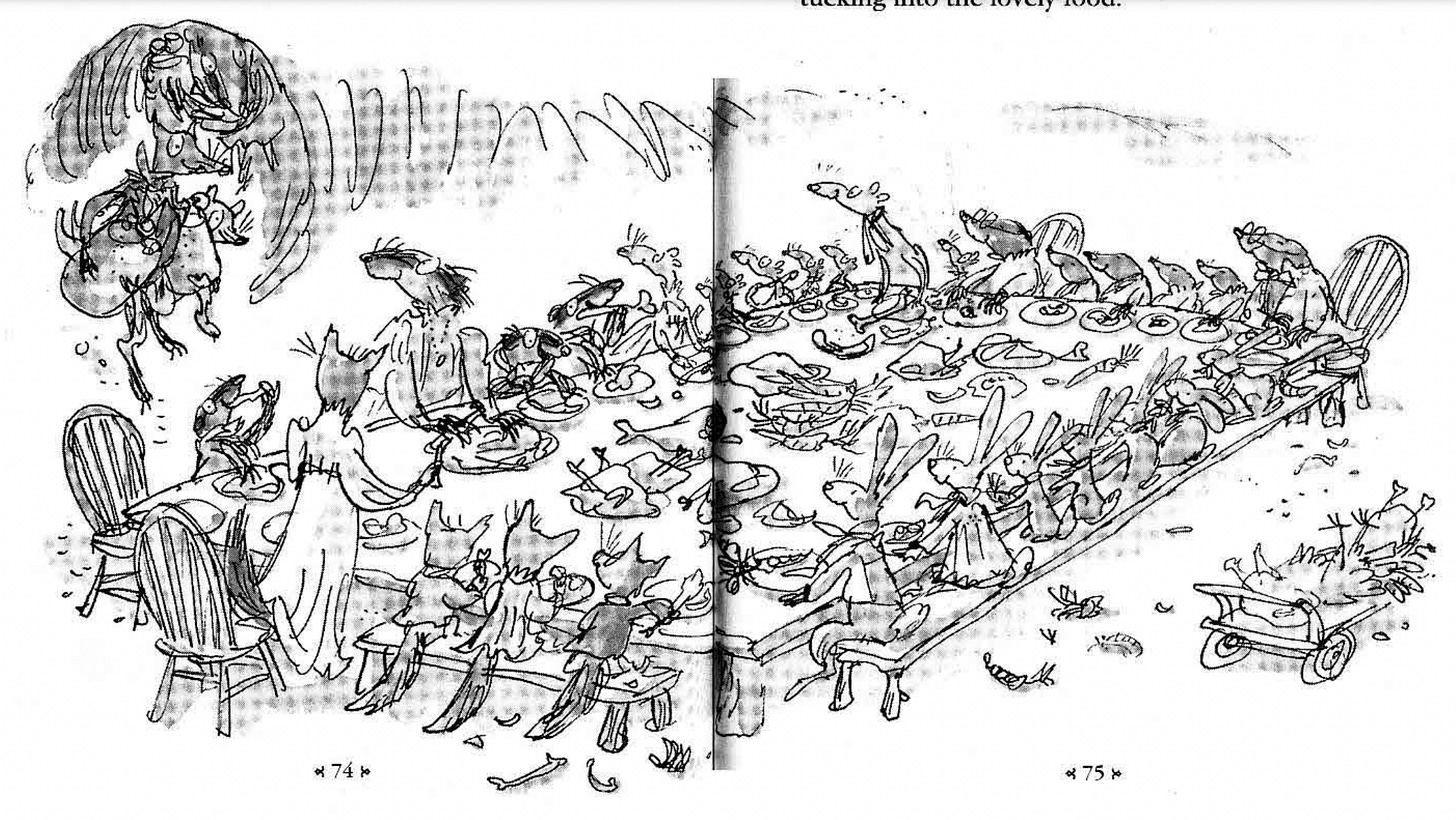

Interest piqued, I decided to revisit Roald Dahl’s original children’s book. But what captured my attention anew, and to my greater dismay, was the recurring problem that is endemic to children’s books: ugly art. Questions of political economy and technological society in the world of Mr. Fox deserve more complete treatment than I am able to give here. But on the topic of art, imagination, and children’s stories, Dahl’s Fantastic Mr. Fox strikes me as a microcosm of a wide-ranging and unfortunately deep-seated conspiracy against the child imagination and enchantment at large. When first searching for the book, you will find almost exclusively some variation, probably color, of the 1996 Quentin Blake illustrated edition. It’s rough, anxious, and generally speaking, not appealing. It’s what we’d call ‘childish’ but is it, really? The Quentin Blake illustrations are mostly formless, chaotic, careless, and irreverent. Although a child looking at them can’t verbalize it or maybe even perceive it, I can’t help but think that the psychological effect is something like a form of neglect – not just neglecting the spirit and imagination, but simply that these illustrations look like scribbles on a scrap piece of paper that’s then thrown to the child, like leftovers to a dog.

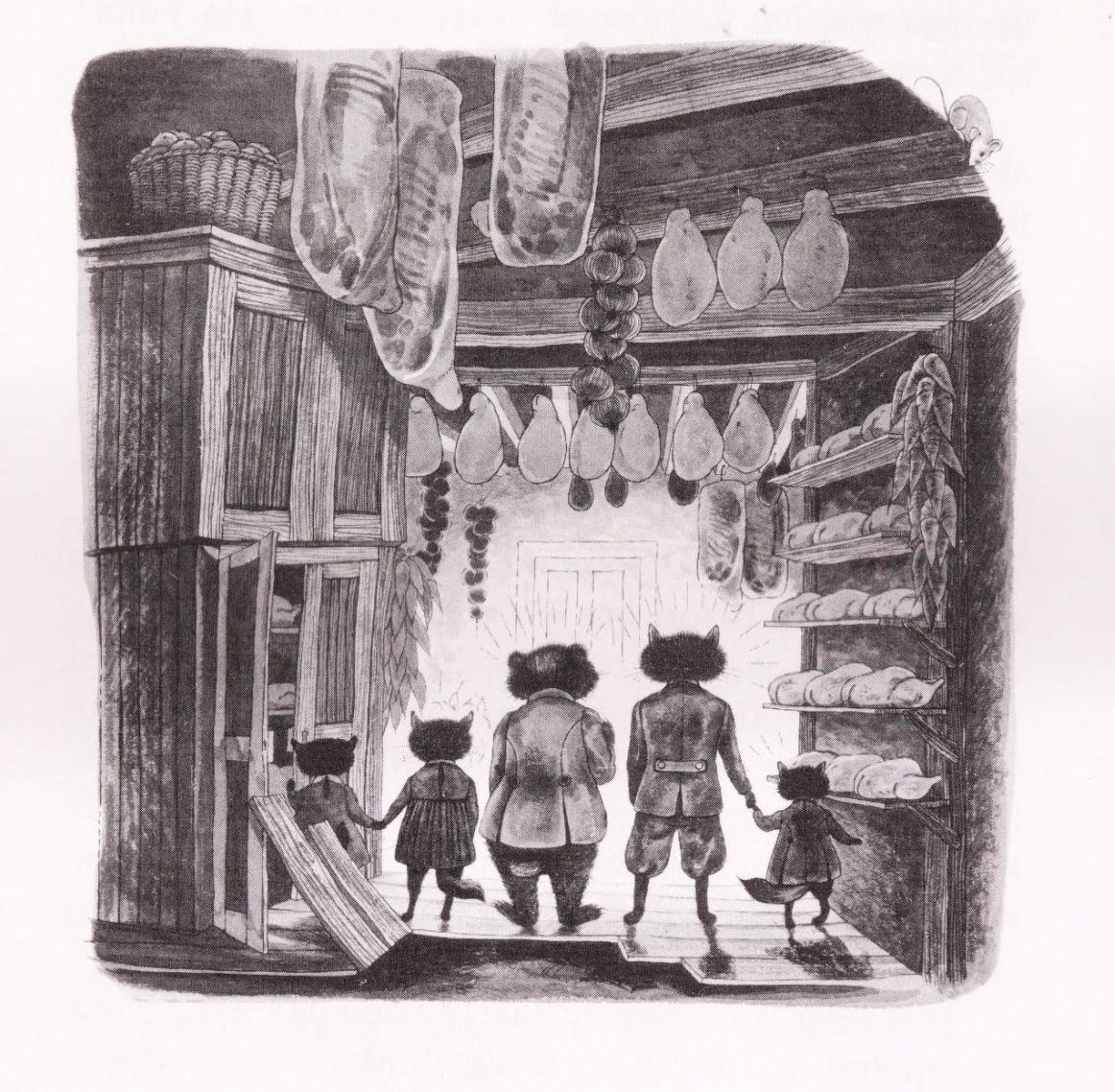

In stark contrast, the first edition, published in 1970, featured illustrations from Donald Chaffin. Unlike Blake’s, the Chaffin illustrations provoke wonder, feature depth, realism, and a whole universe where the characters can be more fully experienced. One can contemplate the images, a child could easily construct stories that branch out of the original book because these images tend to inspire. They place the receiver of the story and image in a world that is truly fantastical.

The contrast between the same scene, illustrations juxtaposed, is startling. The first can’t help but induce a peace and calm, if in an adult then surely to a magnified degree in a child. The latter makes one almost anxious to look at. The eye can hardly linger, much less wander. There is no mystery, just a flatness that inspires a nothingness outside of the image. And so, the imagination is dulled. Rinse, repeat, the process continues apace, children’s book after book. They rob the children of any ounce of detail, of a pathway to wonder, and ask them to ‘think for themselves.’

Tara Thieke has written well on this very problem in children’s books:

Realism has vanished, let alone the mysterious realism which can be found in many of the books written between the late 1940s to the 1970s. When the choice is between serif and sans-serif, the publisher inevitably chooses a sans-serif world. There is no place for the child’s eye to linger because everything has been shorn down…

With all the excessive stimulation and reductionist art, how is a child to hold still long enough to take in any of God’s world, or His word? How can one wait patiently to see a whale on a boat off the coast of New England when they can’t sit still long enough to watch the whale on the television because the very idea of a whale has been made a farce?

It’s striking the degree to which the Blake illustrations resemble noise. There isn’t an ounce of serenity to be found in them, anywhere in the pens strokes, the squiggles and twirls. What can the medium teach the child other than simple sloppiness? And worse, it squashes wonder as there is nothing the discover beneath the image as the child peers in. It feels sterile and uncaring, none of the warmth and nature of Chaffin’s work. Thieke raises this point as yet another assault of the imagination: “But a child’s senses are fluttering sailboats poised beneath the tsunami of modernity. Where are children to find the silence and space to roam without interruption? Where are the creeks in our cities, the gardens, the unmowed meadows?”

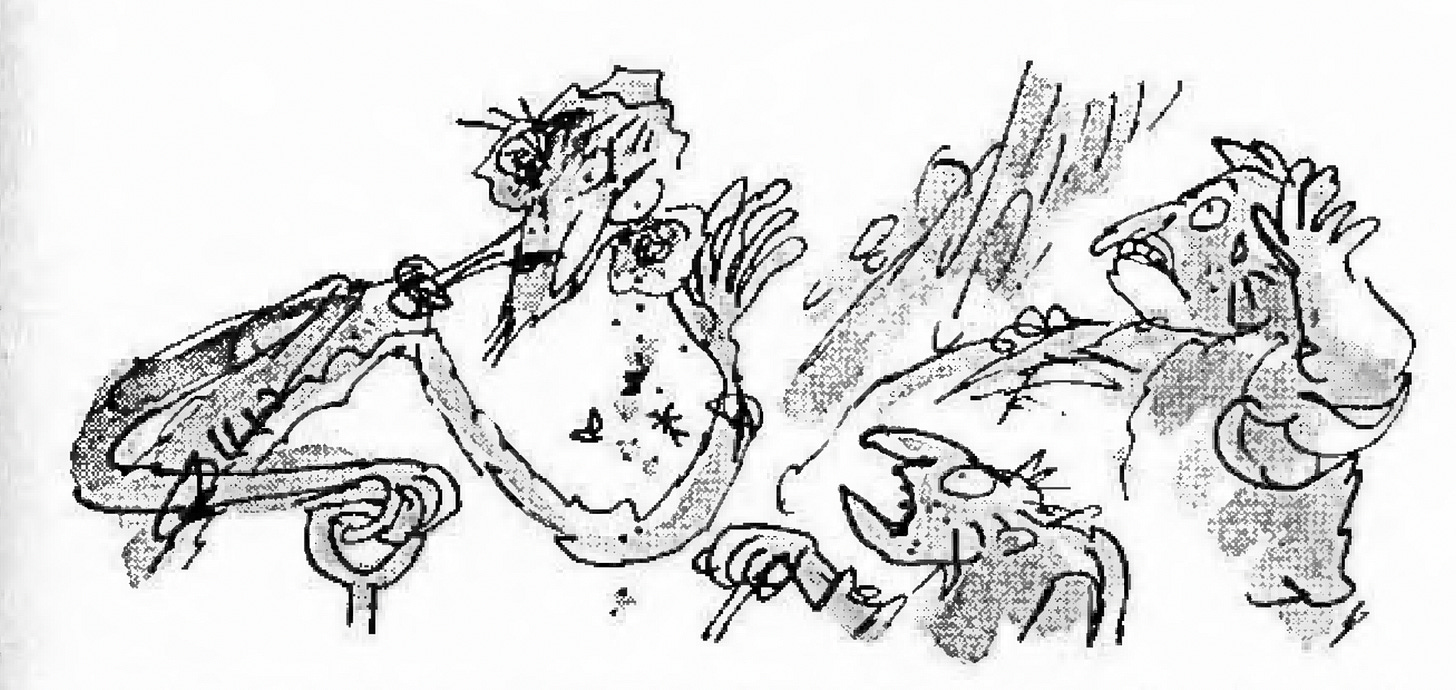

While the farmers are indeed nasty characters, the portrayals of the farmers in the original illustrations still remain on the whole respectful, realistic, and evocative. The Blake illustrations, however, transfer the nastiness of the character into not just the depiction, but the form of it as such:

Not only are the personified and animated characters robbed of their ‘humanity’ by the style, even the humans themselves are portrayed as grotesque in form in the more modern interpretation, to call it.

Thieke once again points to the great danger that is engendered with such children’s books:

Here the child encounters a world of noise, hastiness, and sneers. Perhaps it’s telling that the highest praise in children’s literature seems to be “you’ll die laughing.” There’s nothing to do but point, mock, and laugh. There is a miserable nihilism looming behind “F is for Fart.” Your body is ridiculous, child. You are not fearfully and wonderfully made; look, each animal’s dignity is compromised, they are trapped by the gross machinery of their form.

The child, of course, doesn’t know what is happening to them, or even understands it at all. But this grand process of socialization continues, their experience of the world is shaped at least nominally. That which they see on the page, they reflect out towards the world that they live in. I call it a conspiracy because it appears as a near-deliberate action, ‘art’ created in order to stymie enchantment – foisted by publishers upon children and their families. A conspiracy against a child’s desire to see a world they recognize (and come to love) on the pages of stories they adore, which they can then reflect back into the every day and (not-so-)mundane.